On FICO’s Dubious Explanation of Why it Treats Short Sales the Same as Foreclosures

On FICO’s Dubious Explanation of Why it Treats Short Sales the Same as Foreclosures:

April Charney sent me a link to a post which had a condescending explanation of a recent piece by FICO that warrants further discussion. The FICO article attempted to justify its position that someone who enters into a short sale gets his credit score dinged as badly as for a foreclosure. Yes, you read that correctly. One of the reasons many borrowers go to the effort to arrange a short sale, as opposed to the faster and easier process of “jingle mail” is that they assume that the damage to their credit score will be lower.

Here is the rationale, per FICO’s Banking Analytics blog (emphasis theirs):

But there is a pretty serious problem with their argument. Go look at the itty bitty print under that table. The people that are counted in this study first started looking wobbly in the 2007 to 2009 period. As readers may recall, that was during the big subprime reset period. Those folks were much less salvageable than the current wave of defaulters, who are being hit by traditional causes of default: job loss or wage reductions, divorce, medical emergency, with more than usual in the first category thanks to the lousy state of the economy.

A second reason that it’s dubious to apply conclusions from that period to now is servicers have changed their posture on short sales. Until very recently, they were uncooperative, to the point that in Los Angeles, homeowners would have state in their listings that they were not looking for a short sale because brokers would not even bother showing buyers those homes. They knew the banks would jerk them around and they didn’t want to waste their and their customers’ time. So anyone who got a short sale during this time period had to very persistent and/or very lucky (perhaps in a home with a mortgage on the bank’s balance sheet, where you’d see more willingness to reduce losses than on a serviced loan).

The “very persistent” part bears directly upon the credit analysis. If someone who was in strained financial circumstances had to spend months longer getting a short sale through (versus either a deed in lieu or a foreclosure), their very act of trying to work with the bank would deplete their funds. Since reports on the ground are now that banks are cooperating, borrowers who pursue short sales should on average get out of high (and potentially unsustainable) mortgages faster, which means with more financial reserves, which means lower defaults.

And if you look at this from the lenders’ perspective, this is a ridiculous comparison, because it ignores the loss severities. A short sale might result in a 40% loss (maximum) on a first mortgage, and is often in the 5-20% range. Loss severities on foreclosures on subprime loans have been well over 70% and on prime, over 50% and both are rising because the banks have been dragging out foreclosures in the markets with the biggest falls in housing prices. Those will show even bigger loss severities that history would lead you to believe (attenuated foreclosures means servicers advance more, which means the investors can have over 100% loss severities when you include foreclosure costs. Contested foreclosures in addition routinely produce loss severities of well over 100%. 300-400% is not unusual).

It’s pretty astonishing that anyone takes FICO data seriously, given how badly it performed as a basis for lending decisions prior to the crisis. As Amar Bhide pointed out:

April Charney sent me a link to a post which had a condescending explanation of a recent piece by FICO that warrants further discussion. The FICO article attempted to justify its position that someone who enters into a short sale gets his credit score dinged as badly as for a foreclosure. Yes, you read that correctly. One of the reasons many borrowers go to the effort to arrange a short sale, as opposed to the faster and easier process of “jingle mail” is that they assume that the damage to their credit score will be lower.

Here is the rationale, per FICO’s Banking Analytics blog (emphasis theirs):

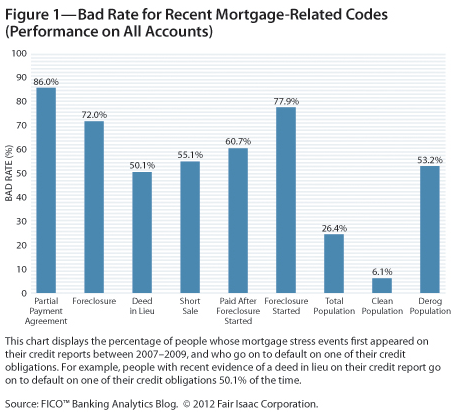

One of the questions we get asked most often is whether it remains appropriate for the scoring model to treat a short sale in a manner similar to a foreclosure….Gee, even though there is a big difference between a 72% default rate and a 55.1% default rate (as in 30%), FICO says this doesn’t matter, 1 in 2 is so bad that they don’t care how much worse nearly 2 in 3 is relative to that.

…we conducted a study isolating more recent occurrences of mortgage stress events. By studying the subsequent performance of these borrowers on all accounts, we determined the credit risk associated with their mortgage events. Looking at data from October 2009 to October 2011, we were able to verify that short sales and other events of recent mortgage distress continue to represent a high degree of risk. These results closely match earlier studies of the risk associated with short sales and other events of mortgage stress.

As the graph below shows, short sales remain extremely risky. However, foreclosures have a bad rate of 72.0% while short sales have a better bad rate of 55.1%. Should that lead to less punitive treatment for short sales?

While it is true that short sales represent slightly better risk than foreclosures, they do not perform well enough to merit a more positive treatment in the FICO® Score. Here’s why. In the population we studied, one out of every two borrowers who experienced a short sale went on to default on another account within two years. That is exceptionally high risk. Additionally, the overwhelming majority of consumers with short sales have some other evidence of mortgage delinquency.

From a weighting perspective, all these mortgage events – short sale, foreclosure, deed in lieu – fall into the same heavyweight class, because they correlate with exceptional riskiness. They aren’t alone in that class either. Based on the data, consumers with short sales perform no better than consumers who have a severe delinquency (90+ days past due), a collection, or a derogatory public record (e.g., bankruptcy, tax lien, etc.) on file.

By comparison, only about one in every 50 borrowers with a score in the high 700s will default on one of their credit obligations. This strong separation of goods from bads is what makes FICO® Scores so useful.

But there is a pretty serious problem with their argument. Go look at the itty bitty print under that table. The people that are counted in this study first started looking wobbly in the 2007 to 2009 period. As readers may recall, that was during the big subprime reset period. Those folks were much less salvageable than the current wave of defaulters, who are being hit by traditional causes of default: job loss or wage reductions, divorce, medical emergency, with more than usual in the first category thanks to the lousy state of the economy.

A second reason that it’s dubious to apply conclusions from that period to now is servicers have changed their posture on short sales. Until very recently, they were uncooperative, to the point that in Los Angeles, homeowners would have state in their listings that they were not looking for a short sale because brokers would not even bother showing buyers those homes. They knew the banks would jerk them around and they didn’t want to waste their and their customers’ time. So anyone who got a short sale during this time period had to very persistent and/or very lucky (perhaps in a home with a mortgage on the bank’s balance sheet, where you’d see more willingness to reduce losses than on a serviced loan).

The “very persistent” part bears directly upon the credit analysis. If someone who was in strained financial circumstances had to spend months longer getting a short sale through (versus either a deed in lieu or a foreclosure), their very act of trying to work with the bank would deplete their funds. Since reports on the ground are now that banks are cooperating, borrowers who pursue short sales should on average get out of high (and potentially unsustainable) mortgages faster, which means with more financial reserves, which means lower defaults.

And if you look at this from the lenders’ perspective, this is a ridiculous comparison, because it ignores the loss severities. A short sale might result in a 40% loss (maximum) on a first mortgage, and is often in the 5-20% range. Loss severities on foreclosures on subprime loans have been well over 70% and on prime, over 50% and both are rising because the banks have been dragging out foreclosures in the markets with the biggest falls in housing prices. Those will show even bigger loss severities that history would lead you to believe (attenuated foreclosures means servicers advance more, which means the investors can have over 100% loss severities when you include foreclosure costs. Contested foreclosures in addition routinely produce loss severities of well over 100%. 300-400% is not unusual).

It’s pretty astonishing that anyone takes FICO data seriously, given how badly it performed as a basis for lending decisions prior to the crisis. As Amar Bhide pointed out:

Statistical models that took no heed of specific circumstances replaced the bankers’ on-the-spot judgments. The use of models also facilitated securitization. Investors could know precisely the values of all the variables (such as the borrowers’ credit scores) for every mortgage that was securitized and didn’t have to worry about the poor judgments of lending officers. Mass production ensured a dependable, high volume supply of the raw material needed..But bankers always prefer to run off cliffs all together, so no one will blame them individually. And therefore relying on third party validators, even discredited ones like FICO and the ratings agencies, is not likely to go away any time soon.

Advocates of high-tech finance continue to applaud judgment-free lending as an advance comparable to Henry Ford’s assembly line. Models, they say, reduce the costs of making lending decisions…

In fact, the mass production of consumer loans isn’t like the mass production of consumer goods. Robo-lending and the securitization it facilitates lead to the misallocation of capital and economic instability. In models used to assess creditworthiness the income of an employee of an auto plant scheduled for closure is indistinguishable from the income of a federal judge. Moreover, not all lending can be easily mechanized. Arguably small business lending has been neglected because it is harder to mass produce than housing loans.

Comments

Post a Comment